“Epistemology” is the study of knowledge. It asks questions like, “How do we know what we think we know to be actually true?” The word is from episteme (‘knowledge’) and logos (‘the logic behind something’). Plato contrasted episteme with doxa – common belief or opinion.

Predictably, the study of knowledge – and its contrast with belief or opinion – has applications for articulating Christian beliefs, for example by helping to provide a framework to justify Christianity as based on knowledge, not opinion.

I was introduced to this debate shortly before I became a Christian, and was in the process of examining the historicity of Christianity’s truth claims. I encountered the work of brilliant polymath Michael Polanyi, who developed an excellent theory of knowledge in his books Science, Faith and Society (1946), Personal Knowledge (1958), and The Tacit Dimension (1966).

Polanyi was a physician who served as a medic in WWI, and then retrained as a chemist for his PhD and went on to become head of the Chemistry and Electrochemistry department in the Institute for Physical Chemistry in Berlin in 1926. However, the political situation in Germany where he lived in the inter-war years led him to become interested in the social sciences, and he went on to emigrate to Britain and became chair of Social Sciences at Manchester University and senior research fellow at Merton College, Oxford.

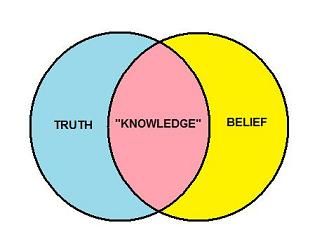

Polanyi was critical of prevailing academic theories of knowledge, which were claiming that knowledge was the opposite of belief. Polanyi disagreed. He argued that all knowledge requires belief. He asserted that you have to commit to believing that a truth claim is true when you apply yourself to accepting it as knowledge. His theory is often shown as a Venn diagram, like this one:

So, Polanyi is saying that truth exists (shown by the circle on the left), and belief exists (shown by the circle on the right).

Critically, he argues that we believe some things to be true which are true. He calls these true beliefs “knowledge” – beliefs which are also truth. This is shown by the intersection of the Venn diagram in the middle.

“Belief is not a magic force which renders anything it touches untrue.”

Polanyi does accept that there also exist some truths which you might not currently believe (shown by the crescent on the extreme left), and perhaps some things which believe but which are not actually true (shown by the crescent on the extreme right), but his central point is that you believe in the things which are true which you accept to be true. Your acceptance of them as truth requires your active engagement in believing them to be true.

Michael Polanyi converted to Christianity partly on the basis of becoming convinced of the reality of Christianity’s truth claims, and partly in reaction to what he saw as a cold amorality in atheist belief systems like Soviet Communism, whose materialistic beliefs about human nature led to the denial of the existence of moral truths.

As I say, I read Polanyi shortly before I too became a Christian. A barrier for me, I think, had been that I had uncritically received from culture the untrue belief that belief is the opposite of truth. This is the false dichotomy which Plato set up when he contrasted knowledge with belief, and which the academic philosophers of Polanyi’s time and New Atheists of our own time subscribe to and assert.

Polanyi’s epistemology helped me to realise that truth is not necessarily the opposite of belief.

“Truth is not necessarily the opposite of belief.”

It can be – as in the case of things you might believe but which are not true, the yellow crescent in the diagram. But beliefs are not necessarily untrue. The things which are true which you believe to be true (Polanyi’s “knowledge”, in the middle of the diagram) are still true. They don’t cease to be true just because you needed belief to accept them as true.

Belief is not a magic force which renders anything it touches untrue. Polanyi concludes that the work of the responsible human being is to test whether their beliefs are true, so that they bring their beliefs in line with truth, enlarging the knowledge section of their Venn diagram ideally until there is nothing left of the untrue belief crescent on the far right.

I think he’d admit, though, despite being a voracious polymath who changed academic career multiple times in pursuit of knowledge, that in this life you will never get round to knowing everything that is true. Tantalisingly, there will always be a little bit of the truth crescent which your knowledge intersection hasn’t quite absorbed yet!

Let that thought sit a while. There are truths which exist which your knowledge hasn’t quite absorbed yet.

There are truths which exist which your knowledge hasn’t quite absorbed yet.

One thought on “Epistemology and Missiology”