The ‘shema’, from Deuteronomy 6:4

The Bible states very clearly that there is only one true God. For example, Deuteronomy 6:4 says, “the Lord our God is One”. This has been the red line of monotheism since, like, forever.

God is God and worthy of worship for a number of reasons. For example, scripture asserts that he is the eternal creator of the universe. Isaiah 40:28 says, “Do you not know? Have you not heard? The LORD is the everlasting God, the Creator of the ends of the earth.” He is everlasting (existed before creation), and created all of creation.

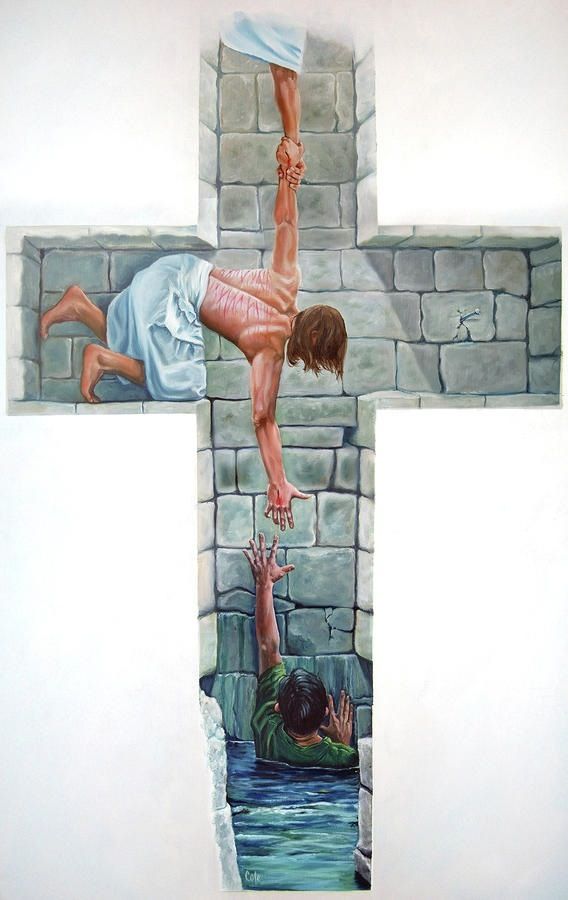

Another characteristic of God that makes God God is that he is our saviour. In Isaiah 45:21, God says, “there is no other God besides Me, a righteous God and Saviour“. Likewise, Jeremiah 3:23 says, “salvation is in the LORD our God”. One of God’s ‘Godliest’ attributes, then, is that he is our saviour.

God’s greatness – as creator and saviour – means he is worthy of our worship. Psalm 145:3, for example, sings, “Great is the Lord and most worthy of praise”. This states a key ontological difference between God and everything else: only God is worthy of worship.

Scripture’s monotheism, then, also condemns worshipping other creatures – even awesome angels – because only God is the creator, only God saves – only God is worthy. Thus Exodus 20:3, for example, commands, “you shall have no other gods besides me”. Worship should be reserved only for God.

“Worship should be reserved only for God”

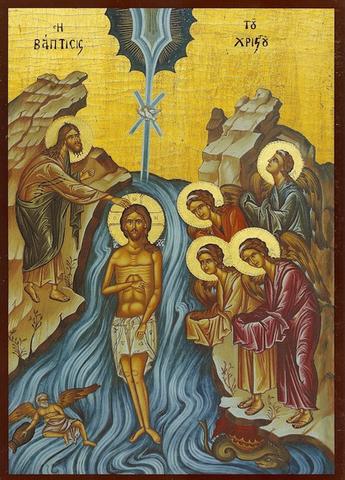

However, the Bible also worships Christ and the Holy Spirit as divine creator and saviour, worthy of praise. For example, John 1:3 says of Jesus “through him all things were made”. In Ephesians 1:13, the Holy Spirit “seals” believers’ salvation. Scriptures like these, in showing Christ and Spirit as being creator and saviour, suggest that Christ and the Holy Spirit are God and worthy of worship.

Nevertheless, Jesus himself is clear that he is the Son of God, and is not the Father. He routinely prayed to his Father, and taught his disciples to do likewise, for example in the famous “Our Father” prayer (e.g. in Matthew 6:9-13). There is, therefore, an undeniable distinction in scripture whereby the Son is not the Father.

And yet, scripture also praises Jesus as worthy of worship, for example in Revelation 5:12, where the voice of many angels, numbering thousands upon thousands, were saying in a loud voice, “Worthy is the Lamb, who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and strength and honor and glory and praise!” In response, “the elders fell down and worshiped” (Revelation 5:14).

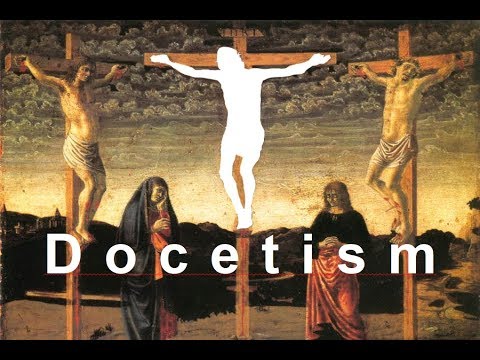

This creates a tension in scripture, then, where God is stated to be one, and worship of anything other than God is idolatry, yet three identified persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) are shown to be worthy of worship.

Unsurprisingly, some confusion arises from this.

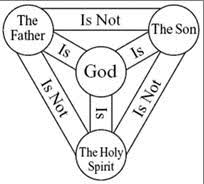

But Christianity reconciles these facts by asserting nine wonderful things:

The Father is God

The Son is God

The Spirit is God

The Father is not the Son

The Father is not the Spirit

The Son is not the Father

The Son is not the Spirit

The Spirit is not the Father

The Spirit is not the Son

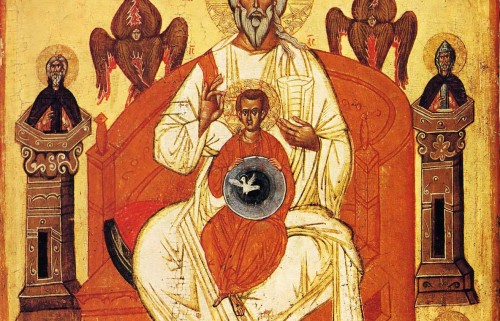

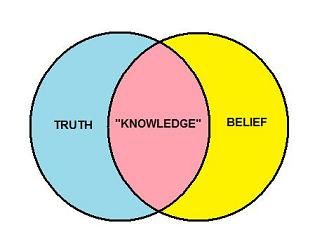

This has been helpfully shown in the following formula:

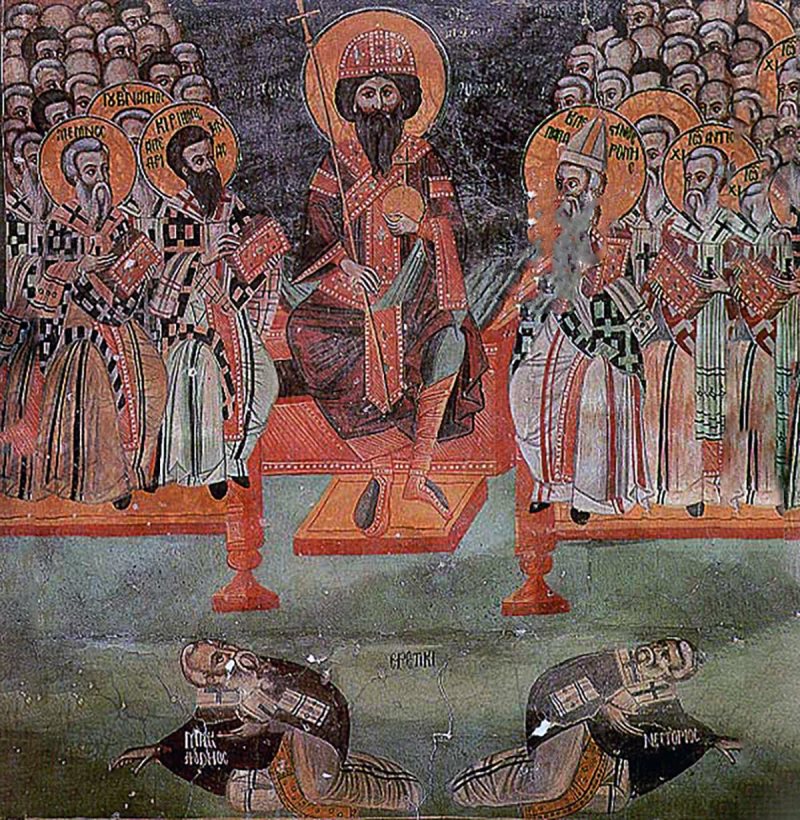

This understanding is called trinitarian Christianity, exemplified for example in the Atahanasian Creed. In my view, it is the only way to reconcile the tension in scripture which I noted above, whereby God is one, yet three persons are worshipped.

The Athanasian Creed therefore states that we worship “one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity”; not confusing the persons (i.e., confusedly thinking the Son is also the Father!), but also not dividing the essence (for example saying the Son is not God):

“For there is one Person of the Father; another of the Son; and another of the Holy Ghost.

But the Godhead of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost, is all one… the Father is God; the Son is God; and the Holy Ghost is God.

And yet they are not three Gods; but one God.”

You can see how the ‘Shield of the Trinity’ above depicts each of these truths – that there are three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) who are distinct from one another as separate persons, but that they are all God, and yet they are not three gods, but one God.

Athanasius’ Creed goes on:

“For as we are compelled by Christian truth to acknowledge every Person by himself to be God and Lord; so we are forbidden to say, There are three Gods, or three Lords.”

Conclusion

In the final analysis, the trinitarian understanding of God neatly synthesises the various statements which scripture claims about the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Scripture shows that there is only one God: “the Lord our God is One” – Deuteronomy 6:4

God is God because he is the creator: “there is only one God, the Father, who is the Creator of all things” – 1 Corinthians 8:6

God is God because he is the saviour: “The LORD is my strength and my song. He has become my salvation. This is my God, and I will praise him” – Exodus 15:2

It is fairly uncontentious to identify God with the Father: “O LORD, you are our Father.” – Isaiah 64:8

However, Jesus is also worshipped as creator: “For by him all things were created” – Colossians 1:16

Jesus is also our saviour: “for today in the city of David there has been born for you a Savior, who is Christ the Lord” – Luke 2:11

Likewise, the Holy Spirit is the creator: “The Spirit of God has made me, the breath of the Almighty gives me life” – Job 33:4

Similarly, the Holy Spirit saves: “God chose you to be saved by the Spirit’s power” – 2 Thessalonians 2:13

Christianity reconciles these facts

Collectively, the above scriptures show that God is one, active and knowable as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as our creator and saviour, entirely worthy of worship.

I see no way of reconciling scripture’s claims about God, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, while remaining a monotheist, unless we use the Athanasian Creed’s trinitarian synthesis of these facts.

The Creed’s first section thus ends, “the Unity in Trinity, and the Trinity in Unity, is to be worshipped.”

Anything else either fails to adequately worship one or more of the persons of the trinity, not praising them as worthy, or separates them out into three gods, thus breaking from monotheism. Father, Son, and Holy Spirit can only be understood as a mystery of three persons in one God.

It matters that we worship God correctly, as only God is worthy of worship. And we should worship the fulness of God – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit – and not overlook the creative and salvific worth of any person of the trinity.