From ‘The Last Judgement’, a triptych by John Martin, created 1851–1853

I’ve just read the Book of Joel, which is only a few pages long, nestled near the middle of the Bible. You can read it very quickly, and it is so worth it. If you don’t have a Bible, you can start online, here.

It opens with the words:

Hear this, you elders;

give ear, all inhabitants of the land!

Has such a thing happened in your days,

or in the days of your fathers?

I chose to look through Joel today because its themes include

- an unprecedented calamity;

- a call to return to worship the Lord, and

- an encouragement for God’s people in their suffering.

So, Joel opens with this cry that something is happening in his land which is unlike anything that had happened ever before in the memory of the people. Joel evokes devastation,

“Awake and weep, like a virgin bride whose bridegroom has died…

describing scenes where “the storehouses are desolate and empty” (1.5, 8, 17), which reminded me of empty shelves in supermarkets. He says, “joy and gladness has been cut off before our eyes” (1.16), and so describes it as

a day of darkness and gloom (2.2)

which is the kind of language we use still today to describe depression and despair.

As I come to the end of my ordination training – a very different end to what I had envisioned – and am anxiously wondering if it will be possible for ordinations to go ahead in September, I was particularly struck by Joel’s priestly language,

“The daily grain offerings and the drink offering are cut off from the house of the Lord; the priests mourn, who minister to the Lord” (1.9)

I’m mourning the bread and wine of communion, and wonder how long it will be before we can meet for a Eucharist.

In Joel, the people are summoned to,

consecrate a fast, proclaim a solemn assembly, gather the leaders and all the people, and cry out to the Lord… gather the people, gather the children and the infants, let the bridegroom come out of his room and the bride out of her chamber…

[in the Torah, certain people like newlyweds are exempt from prayers, military service, and so on while consummating their marriage, but everyone is included in Joel’s summons]

Let them say, ‘Have compassion and spare your people, O Lord, and do not make your people an object of ridicule, a humiliating byword among our enemies. Why should they say, ‘Where is their God?’ (1.12; 2.16-17)

God replies,

‘Even now,’ says the Lord, ‘Turn and come to me with all your heart…

Return to the Lord your God for he is gracious and compassionate,

Slow to anger, abounding in lovingkindness

Then the Lord will have compassion, will answer and say to his people,

‘Behold, I am going to send you grain and wine and oil, and you will be satisfied in full with them’, for he has done great things.

Do not fear, be glad and rejoice, for the Lord has done great things (2.12-13, 18-21)

This, for me, brings to mind a song, Way Maker, which started showing up in churches again relatively recently, and Great Things.

Joel follows this with a beautiful section about the pastures of the wilderness turning green, the trees producing fruit, and pleasant rains falling, (2.22-23), and Joel 2.14 promises God will “leave a blessing, even a grain offering and a drink offering” from the abundance he will provide – he will restore the daily offerings so abundantly that “The mountains will drip with sweet wine” (3.18).

Finally, Joel gives us two fairly famous verses. One is “I will compensate you” for the time of loss, “you will have plenty, and praise the name of the Lord your God who has dealt wondrously with you” (2.26). St. Paul may be echoing this in Romans 8.18, where he says “I consider that our present sufferings are nothing compared to the glory he will reveal to us later.” The other (even more) famous verse from Joel is his prophesy of Pentecost, which St. Peter himself quotes in Acts 2:

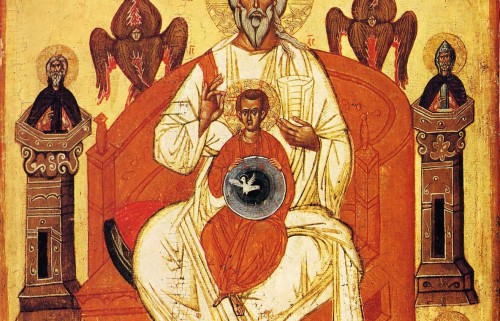

And it shall come to pass,

that I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh;

your sons and your daughters shall prophesy,

your old men shall dream dreams,

and your young men shall see visions.

Even on the male and female servants

in those days I will pour out my Spirit.I will show signs and wonders in the heavens and on earth, and it shall come to pass that everyone who calls on the name of the Lord shall be saved. (Joel 2.28-32; Acts 2.16-21)

Joel ends, then, with words of comfort, that “the Lord is a refuge for his people, and a stronghold of protection”, promising “a fountain will go out from the house of the Lord” (3.16, 18).

Why not read Joel this week, even today, as we anticipate the coming of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost – next Sunday 31st May.

Veni Sancte Spiritus