Some dudes with beards. Stern, but fair

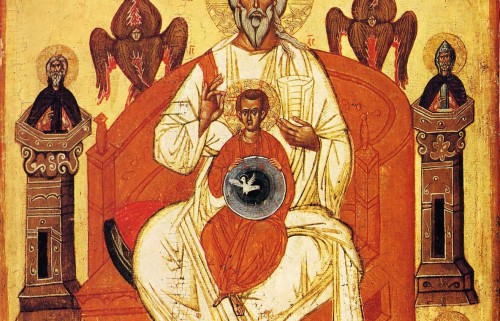

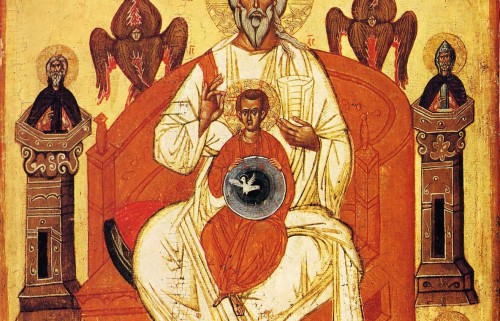

I recently wrote a blog post about the doctrine of the trinity and why it is a necessary synthesis of the claims of scripture that there is only one God, and that Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are all divine persons, for example in the work of creation and salvation, and are thus worthy of worship.

I thought it might be fun to follow up with a blog post or two about some historic heresies which still pop up from time to time today, and outline why their understanding of God is inadequate compared to orthodox Christian belief.

So, here is my first list of three Christological heresies, and why they are wrong…

1. Subordinationism:

This heresy claims that Christ the Son is not equal to the Father.

Key dates: 1st-4th Centuries

Key supporter: Arius of Alexandria

Key text: “My Father is greater than I” (John 14:28)

Implications: Christ is not God

Examples: LDS (Mormons)

Answer:

The fact that the Son consents to do the will of the Father does not prove he is inherently inferior to the Father. Scripture shows that the Son shares the Father’s divine nature and is therefore ontologically equal with the Father, by nature.

Key dates for answer: 320, First Ecumenical Council (the First Council of Nicaea) and 381, the Second Ecumenical Council (the First Council of Constantinople)

Key hammer: Athanasius of Alexandria

Key text: “all may honour the Son, just as they honour the Father. Whoever does not honour the Son does not honour the Father” – John 5:23

Implications: the Son is equal to the Father in divine nature. He is therefore God, worthy of worship.

However, the Son consents to be ‘relationally’ and ‘operationally’ subordinate to the Father, despite their equality of natures.

For example, Christ is the mediator between God the Father and humanity, so that he can bring us to the Father.

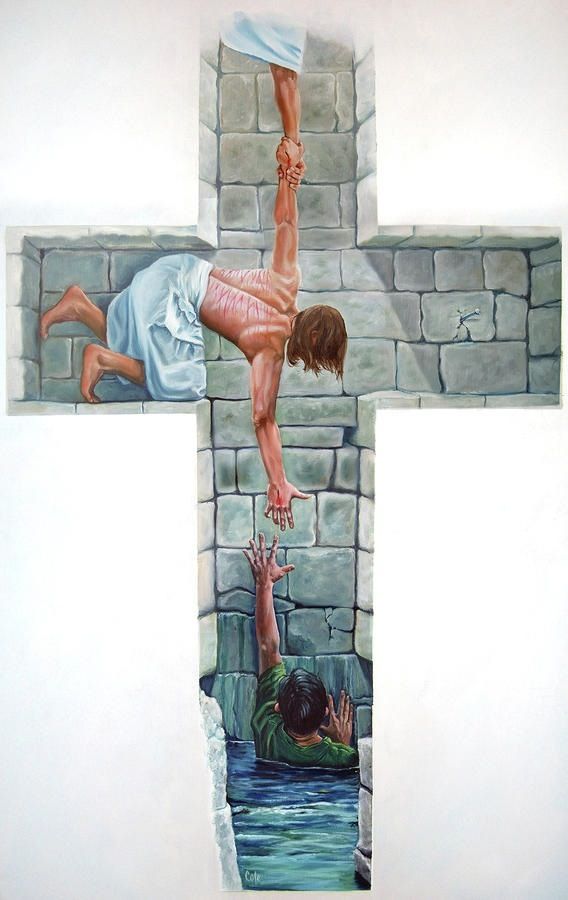

“Christ is the mediator between God the Father and humanity, so that he can bring us to the Father.”

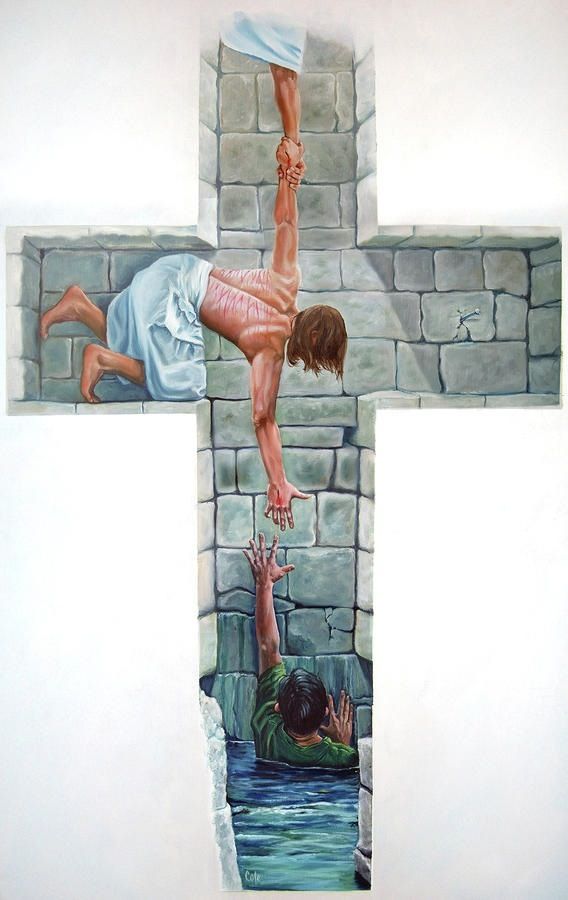

Nevertheless, only God is good enough to pay the price for our sins. So, for Christ’s death on the cross to be enough to pay for our sins, he has to be God in incarnate.

In subordinationism, Christ cannot offer salvation. In Christianity, that is exactly what he offers.

2. Adoptionism:

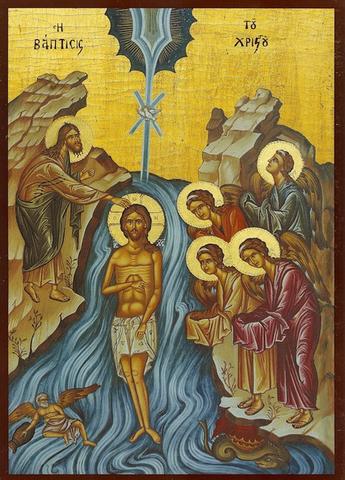

This heresy claims that Jesus was just a human, and that God chose (‘adopted’) him to be the Messiah, perhaps because of exceptional goodness or faithfulness on Jesus’ part. Adoptionists vary as to when they think Jesus was chosen – possibly at his baptism, possibly the transfiguration, possibly some other time.

Key dates: 2nd & 3rd Centuries

Key supporter: Praxeas

Key text: “You are my son; today I have become your father.” – Psalm 2:7

Implications: Christ is not God.

Examples: Christadelphians

Answer:

Jesus is God incarnate. Scripture asserts this repeatedly.

Key date for answer: 213, ‘Adversus Praxean’

Key hammer: Tertullian

Love the hair, Tertullian

Key text: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” – John 1:1

Implications: Christ is God come to Earth. This means that God is not uncaring and distant, but reaches out to us and can be known. Additionally, as with subordinationism above, only God is good enough to pay the price for our sins. So, for Christ’s death on the cross to do this, Christ has to be God incarnate.

3. Arianism:

This heresy claims that Christ was created by the Father at some point in time. Even if he is semi-divine, he doesn’t have the same divine nature as God, and is a junior god at most, or maybe just an angel.

Key dates: 3rd & 4th Centuries

Key supporter: Arius

Key text: The LORD made me as the beginning of His way, the first of His works of old. – Proverbs 8:22

Implications: Christ is not God

Examples: Jehovah’s Witnesses

Answer:

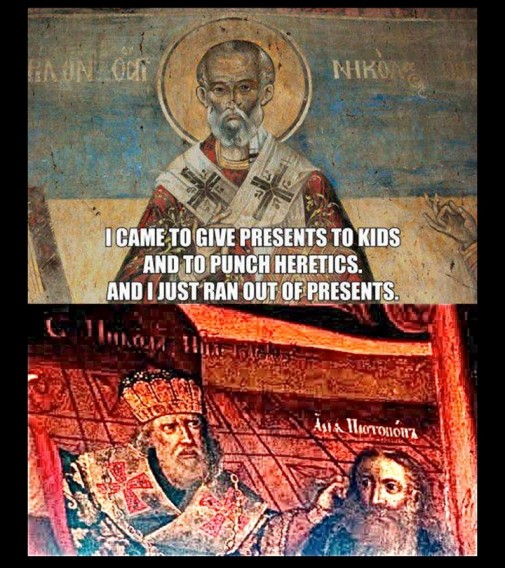

We can deduce from scripture that the Son is of the same – co-eternal – substance as the Father. Although he is a different person to the Father, scripture shows they are both part of the same one God.

Key dates for answer: 320, First Ecumenical Council (the First Council of Nicaea) and 381, the Second Ecumenical Council (the First Council of Constantinople)

Key hammer: Athanasius

Key text: “I was set up from everlasting, from the beginning” – Proverbs 8:23

Implications: Because the Son is consubstantial with (of the same divine nature as) the Father, they are equal by nature. As with the answer to subordinationism above, which is closely related to Arianism, just because the Son chooses to do the Father’s will does not mean he is of a different, inferior nature. They are equally God.

To some people, the debate over whether Christ is of the same or similar nature to the Father has seemed like a fairly insignificant debate. Arianism admits that Christ is of a “similar” nature to the Father, the first creature created, and therefore very important. It might seem like splitting hairs to insist that he is not just of “similar” nature but of “the same” nature.

Nevertheless, in terms of salvation, this is essential. As with the answers to subordinationism and adoptionism above, only God is good enough to pay the price for our sins. For Christ’s death on the cross to be sufficient, he has to be God incarnate, not a ‘semi-divine’ junior ‘god’ who is “similar” to God. Christ has to be God incarnate for the crucifion to be enough.

Conclusion:

There is a common theme throughout all three of these heresies, and a common reason for rejecting them. The common theme is that they all claim that Christ is not God, whereas orthodox Christianity points out that Christ has to be God incarnate for his death on the cross to adequately pay the price for our sins.

If Christ is somehow ontologically inferior to God, like a human adopted by God, or just a semi-divine being or angel who is not God, then he isn’t good enough to pay the price for all our sins. We need Christ to be God, and the fact that he is God incarnate means that he alone can pay the price for our sins.

Pray: Hallelujah. Thank you Lord that you took on human flesh and came to the earth you created, walked among us, taught us and guided us, and healed and delivered us from our sicknesses and demons. Thank you for taking our sins on yourself, suffering brutal death so the price of our guilt is paid. Thank you that your resurrection proves you have power to defeat death, and promises our own resurrection to life forgiven by you.